MILWAUKEE — One century ago, Wisconsin women pushed their state to the forefront of the equal rights movement.

What You Need To Know

- In July 1921, Wisconsin was the first state to pass an equal rights law for women

- The move came after decades of women campaigning for suffrage and other rights

- Wisconsin was also the first state to ratify the 19th Amendment to give women the vote

- The equal rights law wasn't a perfect solution, but still a groundbreaking move for the time

After years of hard work and intense campaigning from suffragists, women across the country had just won the right to vote, with Wisconsin the first state to ratify the 19th Amendment.

And in July 1921, then-Gov. John Blaine signed off on another measure that would move the Badger State even further: An equal rights bill promising that “women shall have the same rights and privileges under the law as men.”

It was the first law of its kind to pass in any U.S. state, and women’s rights advocates far and wide celebrated its success. “This makes Wisconsin the only spot in the United States where women have, or ever have had since the beginning of our country, full equality with men,” National Woman’s Party leader Alice Paul wrote to advocates in the state.

Of course, the step toward gender equality didn’t come for free. And it was far from a perfect solution to the challenges women faced.

Here, we take a look at the work that led up to the groundbreaking law and the complicated legacy that has played out for the past 100 years.

Beginning the fight

Women’s rights had been an issue for Wisconsin starting from its earliest days as a state.

As leaders were hashing out Wisconsin’s constitution in 1846, some suggested that the brand-new state should give women property rights and even the ability to vote. But by the time a final draft was approved, these measures had gotten the chop, as some opponents thought giving women more rights could “upend the natural order of the family,” historian Erika Janik writes for WPR.

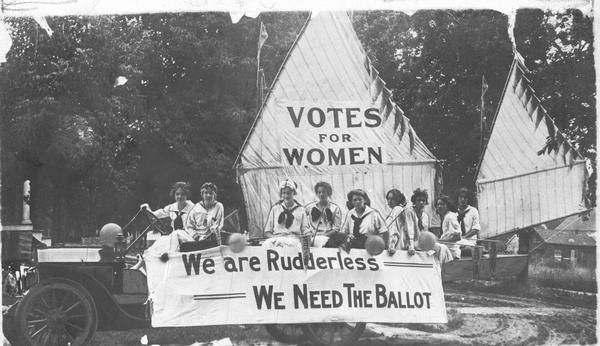

Still, Wisconsin women didn’t give up on the fight for equal rights. In the late 19th century, women started forming organized suffrage groups to campaign for the vote.

Leaders like Ada James, Theodora Winton Youmans, and Belle La Follette -- whose husband, Robert, championed progressive causes as Wisconsin governor and senator -- brought together a broad coalition of women across the state.

The movement united a wide range of women’s groups, and also included different ideas about how to argue for suffrage, said Nancy Unger, a professor of history at Santa Clara University who has written biographies of both Belle and Robert La Follette.

“There are lots of women who are campaigning for the vote because they say it will allow them to carry out their natural sphere as the uplifters, the civilizers, the moral ones,” Unger said. “‘We just want to be the best wives and mothers we can be.’”

On the other hand, Unger explained, some suffragists argued that women should get the vote because, well, they’re people, too: “‘Read the Constitution. All people are created equal. We should have equal rights, and that’s all there is to it.’”

By the turn of the century, women’s rights campaigners had won a partial victory. Wisconsin would let women vote, but only in school elections -- something more in their “rightful domain.”

Belle La Follette was hopeful that this was just the first step for Wisconsin’s women. “Don’t fold your talent in a napkin,” she encouraged women voters in a column. “If you vote when you have an opportunity, the opportunities increase.”

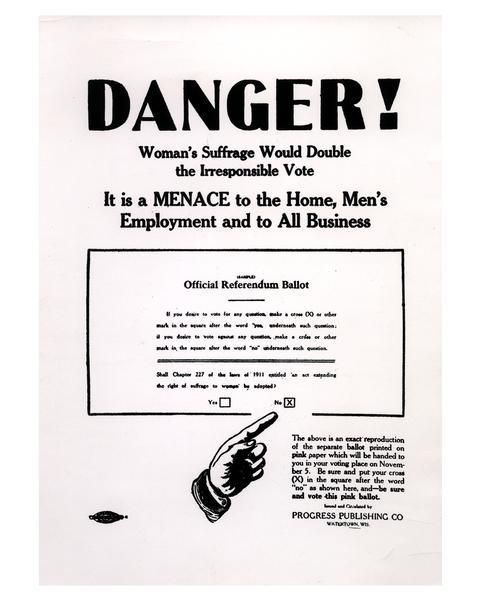

But getting to full suffrage would prove to be more of a challenge. In a 1912 referendum in Wisconsin, men in the state voted against women’s suffrage by a wide margin -- proving that even in a state like Wisconsin, which at the time was a leader in the progressive movement, women’s rights were not going to be given out without a fight.

Picking up steam

Though suffragists lost the battle in Wisconsin, they’d end up winning the war by taking their fight to the national level.

Instead of focusing only on their own state, La Follette and other Wisconsin leaders took their show on the road, Unger explained, campaigning across the U.S. to get a national amendment through Congress. In some cases, they teamed up with more radical advocates like Paul, who marched, went on hunger strike, and even got arrested while picketing outside the White House.

Finally, in 1919, the 19th Amendment passed in the Senate, with Belle La Follette looking on from the balcony. She was quick to reach out to the Wisconsin legislature and get them to ratify the amendment before anyone else, beating out Illinois by hours.

The victory for women’s suffrage -- and the fact that society didn’t collapse when women got the vote, as some critics had warned -- gave momentum to the broader women’s rights movement, Unger said.

“For some, getting the vote was it. That was all that they wanted,” Unger said. “But for others, it’s like, ‘No. This is a crucial step, and now let’s really go for full equality.’”

Women now held direct political power, and candidates openly tried to win them over, as Tamara Raymond explains in a 1982 article. Blaine was elected as governor in 1921 on a platform of advancing women’s rights, and Wisconsin women held him to his promise.

Mabel Putnam, the state chair of the Woman’s Party, started making rounds to drum up support among lawmakers for an equal rights bill. She met with Charles Crownhart, who agreed to write up the legislation -- a broad law that would serve as a “woman’s bill of rights.”

One central question caused some trouble: If we recognized women as fully equal to men, then how could we still offer special protections to women? The bill tried to have it both ways, recognizing that “equal does not mean the same,” Unger said.

When the bill was introduced to Wisconsin lawmakers in May 1921, it promised that women would have equal rights “in the exercise of suffrage, freedom of contract, choice of residence for voting purposes, jury service, holding office, holding and conveying property, care and custody of children, and in all other respects.”

It also said that statutes applied to men should “include the feminine gender unless such construction will deny to females the special protection and privileges which they now enjoy for the general welfare.”

The bill was still met with some pushback. One state assemblyman argued that the bill would “result in coarsening the fiber of woman” and take her out of her “proper sphere.” But with the fierce advocacy of Putnam and other leaders, the bill was passed by state lawmakers in June 1921 and signed into law by Gov. Blaine shortly after.

A mixed legacy

As the first equal rights bill in the U.S., the Wisconsin law marked a big milestone for women’s rights and was celebrated across the country.

A newspaper article at the time proclaimed that with the bill’s signing, “Wisconsin became the first state in the Union where women have equal rights with men under the civil laws.” The National Woman’s Party celebrated that “centuries of legal precedent and tradition, built upon the conception of women as inferior beings … have been overturned by Wisconsin with one clean stroke.”

Of course, the truth was not so simple, Unger said.

The law would successfully extend new rights to women, like the ability to hold office and perform jury duty. In one case tried before the Wisconsin Supreme Court, judges decided that the law allowed women to sue their husbands in case of injury by them.

But, through some “skillful maneuvering,” some used the bill’s own language to chip away at it, Unger said.

The choice to have it both ways -- to give women equal rights while still allowing them extra protections -- became a bit of a loophole to work against reform. In a 1923 case, the state attorney general ruled that it was fair to keep women out of legislative employee positions because doing so would shield women from working “long and unreasonable hours.”

“They’re protecting women right out of jobs,” Unger explained.

Plus, even after Wisconsin set the precedent, other states didn’t fall in line to pass their own bills. Suffrage leaders did write up a national Equal Rights Amendment shortly after Wisconsin’s law succeeded -- but to this day, the federal ERA is still in limbo.

The same challenges that crippled Wisconsin’s law have also been raised over nearly a century of debate over the ERA, with critics saying it would stop the government from recognizing any difference between men and women.

All in all, the groundbreaking bill has left a bit of a mixed legacy, Unger said.

“The legacy is, the state did pass an equal rights act. I mean, that’s pretty impressive,” Unger said. “But, I think, there’s also a cautionary tale.”

The 1921 law was certainly a big achievement for the Badger State, and one that cemented its status as a progressive leader for its time. For Wisconsin’s 3 million women, though, the journey toward equality continues to this day -- especially as the COVID-19 pandemic has set back some of the progress toward gender equality, with women dropping out of the workforce at higher rates and struggling to keep up with the demands of caretaking.

As the acclaimed writer and Wisconsin native Zona Gale described it back in the last century: “The status of women in Wisconsin, even under our Equal Rights Law, is but a stage in that long march.”